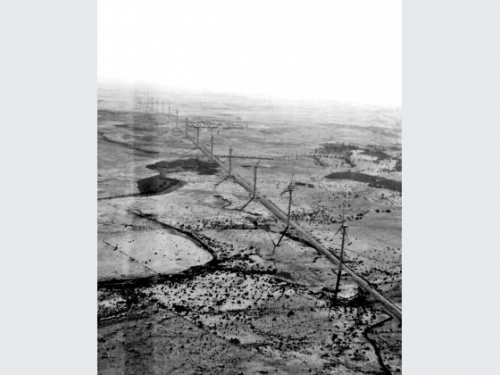

The US and China are already working together on the clean-energy project Sapphire Wind in Pakistan, where Beijing and Washington want Pakistan to grow its economy and undermine extremism. PHOTO: SAPPHIRE WIND

With Mr Donald Trump’s election, China and the United States could be on a collision course. The US President-elect promised during the campaign to label China a currency manipulator, instruct the US Trade Representative to bring cases against China in the World Trade Organisation and threaten 45 per cent tariffs if China does not renegotiate trade agreements with the US. Meanwhile, China pursues a military build-up in the South China Sea designed to diminish US influence in Asia.

As Mr Trump addresses trade and the other issues on the US-China agenda as president and not candidate, he may find it useful to look for areas where the two countries could work together.

One opportunity ready to be explored is the vision promoted by both Beijing and Washington of the need for more economic and infrastructure connections between East Asia, South and Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Two concepts are in play: China’s One Belt, One Road, or Obor initiative, a multibillion-dollar programme to build ports, railways, roads, power plants in and around 60 countries and the more modest, but still important, American New Silk Road initiative, or NSR.

In July 2011, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke in India about the benefits of linking Central Asian economies with those in South Asia, with Afghanistan and Pakistan in the centre. Increased regional economic connectivity, she argued, would promote sustainable economic growth, a crucial part of the effort to defeat extremism.

In September, the US convened a NSR ministerial meeting in New York and China expressed enthusiasm for the project.

Turkey hosted the Heart of Asia Conference in November 2011 and, supported by the US and China, the concept became a touchstone for regional cooperation.

Obstacles then emerged. The Chinese said the name New Silk Road “belonged to China” and “Historic Trade Routes” would be a better name for the US initiative.

In 2013, Chinese leaders responded with a Silk Road initiative of their own: One Belt, One Road consists of two main components — a land-based Silk Road Economic Belt and a sea-based Maritime Silk Road — which Chinese leaders believe will together change the geostrategic and geo-economic face of the region.

BENEFITS FOR AFGHANISTAN AND PAKISTAN

In August this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that more than 100 countries and international organisations had committed to participate in Obor.

According to Chinese press reports, Obor is supported by US$40 billion (S$56.7 billion) from China’s Silk Road infrastructure fund, US$100 billion in Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank pledges, and an initial US$50 billion commitment from the New Development Bank of the Brics countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — with a promise to increase that to US$100 billion.

The US and Chinese projects are currently on separate trajectories. American officials maintain that they support Obor, though the US is rightly wary of projects that enhance China’s military capacity. And the US cannot match the dollars or yuan pledged or spent.

That said, there are several strategic, regional and commercial benefits to additional US-China cooperation around the Obor and NSR initiatives.

For example, the US-China Summit in Hangzhou in September highlighted Afghanistan as an “area of cooperation”.

The two countries share an interest in an Afghan state in which Al Qaeda and Islamic State find no havens, drug exports shrink and private sector–based economic activity increases.

A coordinated Obor-NSR effort to create what Afghan officials once called an “Asian Roundabout” to encourage a sustainable Afghan economy would promote these shared goals. The recent opening of a rail line from the eastern coast of China to the northern Afghan city of Hairatan, offers Afghan exporters an alternative route to Asia with dramatically reduced transit times.

Another area of potential cooperation is Pakistan, where China and the US want Pakistan to grow its economy and undermine extremism.

China’s US$51 billion commitment to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is designed to build highways, railways and energy generation in Pakistan, including a proposed rail link and highway between Pakistan’s port at Gwadar and China’s north-western region of Xinjiang, which would also connect the Obor to China’s Maritime Silk Road project.

Pakistanis hope the corridor will create 700,000 jobs by 2030 for some of Pakistan’s 190 million people, a majority of whom are under the age of 22.

Washington and Beijing are already working together in Pakistan on the clean-energy project Sapphire Wind.

The US Overseas Private Investment Corporation has provided US$128 million for this 50MW wind project, which uses General Electric turbines.

Under the umbrella of the US-Pakistan Clean Energy Partnership, the US will invest US$70 million on transmission lines to connect a 680MW wind project in Sindh to the national grid. China is also an investor.

Collaborative NSR-Obor efforts between the US and China can benefit US companies. The Wall Street Journal reported in October that General Electric, Honeywell and Caterpillar are already focused on the possibilities. According to the Journal, GE’s orders in Pakistan are more than US$1 billion today, compared with less than US$100 million five years ago.

Connecting US firms to Obor and keeping them aware of NSR opportunities require a concerted effort by the US government, including the Departments of State and Commerce, the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation and the Export Import Bank.

POTENTIAL CHALLENGES

Despite the obvious benefits, there are many challenges to creating an NSR-Obor nexus. China may be pursuing Obor to control rising wage rates at home by exporting employment and soaking up overproduction in industries like steel.

The Chinese might decide to go it alone, with the enormous resources they have promised against a small US investment in NSR. The number of American firms interested in Obor may be too small to reach critical mass and those that seek engagement may stand no real chance to work with Chinese companies, especially state-owned enterprises.

In September, representatives of 10 Chinese state-owned enterprises visited Washington and New York to promote US commercial interest in Obor opportunities, but more needs to be done by Beijing to welcome US private-sector participation and protect US commercial interests.

Another challenge is managing Indian anxieties about Obor. Many analysts in Delhi see Obor not as a development initiative, but as a strategic effort by Beijing to surround India with naval facilities in Gwadar in Pakistan, Colombo in Sri Lanka and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar.

The possibilities of joint efforts inspired by Obor and NSR present the incoming Trump administration with a strategic opportunity to improve US-China ties, advance common security interests and create economic opportunities for American business.

Success would bring tangible benefits to a region where further state failure would surely fuel extremism, a threat to both the US and China.

And, not least, there would be something positive on President-elect Trump’s already contentious agenda with China when he takes office in January.

Ambassador Marc Grossman is a Vice Chairman of The Cohen Group. A US Foreign Service Officer for 29 years, he was the US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan (2011-2012) and a Kissinger Senior Fellow at Yale in 2013. This article was first published in Yale Global Online.